Around and Back Again: How Anti-Vaccine Narratives Go Global

Authors: Lindsay Hundley and Toni Friedman (Stanford Internet Observatory)

Mis- and disinformation surrounding COVID-19 vaccines is a global phenomenon. One explanation for this trend is that COVID-19 vaccine discussions impact every person around the world. Recently, for instance, news of a 13 year-old’s death days after receiving the vaccine went viral on two separate occasions, both domestically and internationally. In this post, we use this case and others to explore how shared anxiety around COVID-19 encourages the spread of anti-vaccine narratives across languages and communities.

How a Single Story Goes Global

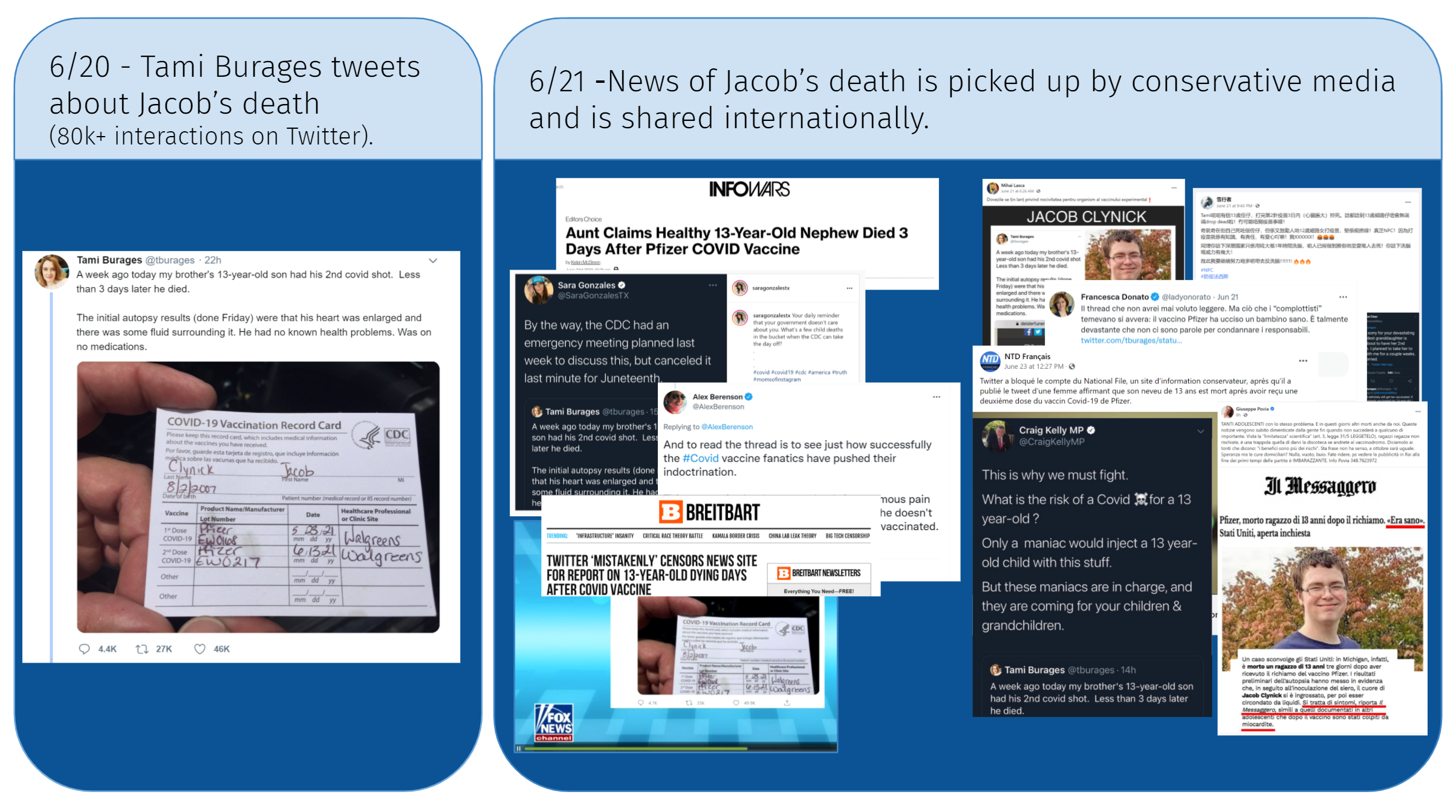

The story of Jacob Clynick, a 13 year-old boy from Michigan who died a few days after his 2nd COVID-19 shot, illustrates how content promoting vaccine hesitancy can go global. On June 20, Jacob’s aunt, Tami Burages, tweeted a thread detailing Jacob’s death, noting that he had no medical conditions and called on the CDC to investigate. While Burages emphasized that she is pro-vaccine, right-wing anti-vaccine communities quickly picked up the story. The following day a TV host for the conservative media outlet, Blaze Media, claimed the CDC had cancelled an emergency meeting to investigate Jacob’s death to celebrate Juneteenth instead. On Instagram, the host reposted the tweet with the caption, “Your daily reminder that your government doesn’t care about you. What’s a few child deaths in the bucket when the CDC can take the day off?” InfoWars, Nationalfile, and Breitbart also circulated the story, as well as anti-vaccine influencer Robert F Kennedy Jr. Burages deleted her original thread, but it appears the thread had been liked over 50,000 times, retweeted over 35,000 times, and received nearly 5,000 comments before it was deleted.

Figure 1: Original tweet sharing news of Jacob’s death (left). A collage of domestic and international coverage of Jacob’s death the following day (right).

On June 21, a day after Burages’ first tweet, Jacob’s death was also picked up and circulated in dozens of languages—some of which perpetuated false or misleading claims which we chose not to link to in this post— including German, Romanian, French, Italian, and Chinese. Politicians in Romania and in Italy spread the story on social media. Non-English accounts used the reports of Jacob’s death not only to promote the belief that vaccines are extremely dangerous to children, but also advance the idea that pharmaceutical companies and governments are withholding evidence of harm. An Italian member of Parliament tweeted, “The thread I never wanted to read. But what the ‘conspiracy theorists’ feared comes true: the Pfizer vaccine killed a healthy child” (translated).

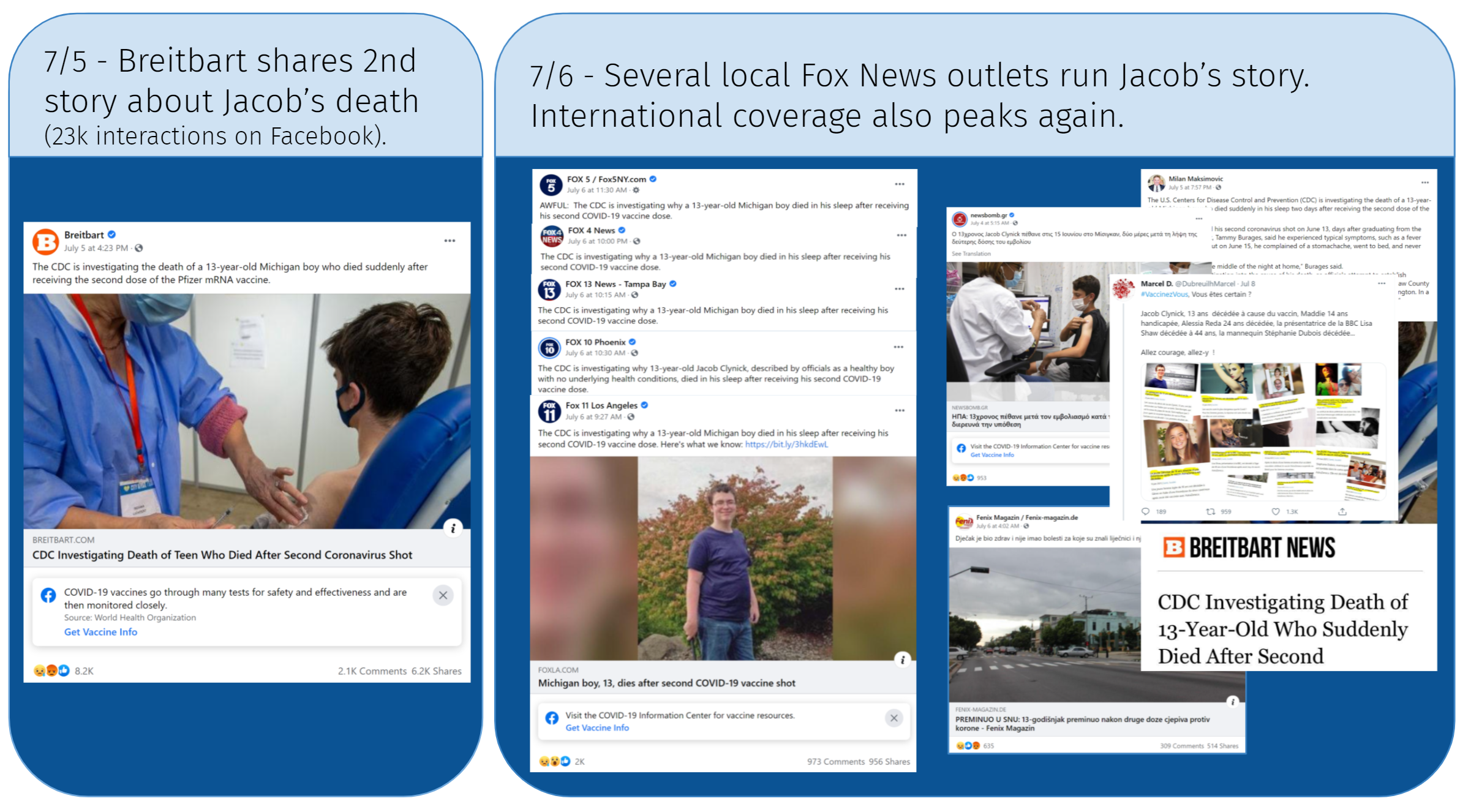

Figure 2: Breitbart shares a second article on Jacob’s death (left). A collage of domestic and international coverage of Jacob’s death the following day (right).

The persistent anxiety around children’s health in particular allowed Jacob’s story to go viral a second time both in the US and abroad, even in the absence of new details to the case. On July 5, two weeks after news of his death originally spread and online chatter tempered off, Breitbart shared a second article calling attention to the CDC investigations into the case. This article generated nearly 23,000 interactions on Facebook and was re-shared in several different languages. There were still no updates from the CDC, but the next day several local Fox News pages shared the story on Facebook, garnering at least 40,000 interactions from their posts alone. Public posts on Facebook mentioning “Clynick” in languages other than English spiked to nearly 28,000 interactions on July 6, including posts by news organizations in Argentina, Bosnia, Greece, and Italy. This demonstrates how attention towards an individual story can spike at a later time, even with minimal new developments to the facts of the case, reigniting feelings of anxiety around the vaccine.

A Global Network of Anti-Vaccine Groups

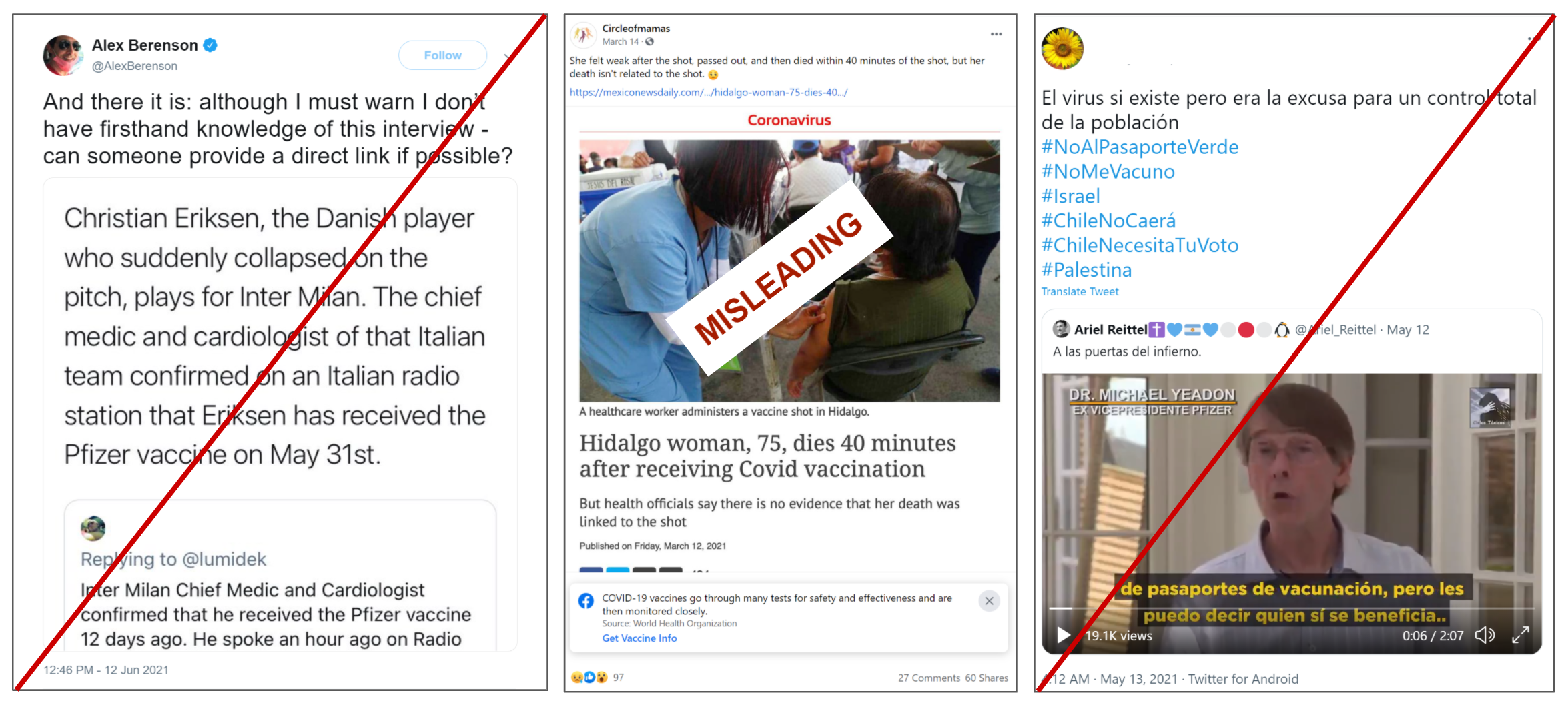

In six months of monitoring, Virality Project analysts have seen anti-vaccine communities pick up similar real life events, like Jacob’s death, from all around the globe and spin them to support anti-vaccine narratives. We have identified online chatter around real or alleged cases where individuals experienced medical complications after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine in over a dozen of different countries, even when links between the vaccine and complications are unrelated, unproven or dubious.

Anti-vaccine advocates often strip these real life events of important context to portray them in misleading ways in order to undermine confidence in the safety of vaccines. For example, in January, prominent anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy shared news about several elderly people in Norway who died shortly after receiving COVID-19 vaccines, even though Norwegian health officials indicated that the deaths were not related to the vaccine. Other times, anti-vaccine users veer into making more demonstrably false claims. After a nurse in Tennessee with an unrelated medical condition fainted during a TV interview on receiving the vaccine, one Facebook user shared the video with the caption, “Watch this nurse pass out after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. It’s so safe though, right? This will become a mass genocide if people continue to follow these rabid dictators.” Other anti-vaccine accounts started a rumor that the nurse had died shortly after (she did not). This story spread so widely among domestic and international audiences that it has been fact-checked by dozens of organizations from around the world, including those in Australia, France, India, Israel, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

News of medical complications following COVID-19 vaccines is not the only type of vaccine-related content that spreads internationally. Other common narratives with international spread include unsupported claims from anti-vaccine medical doctors. In a recent example, doctors affiliated with a fringe, “alternative information” organization in Spain falsely claimed to find evidence that the majority ingredient in Pfizer vaccines is a toxic compound. This claim circulated internationally, spreading in Spanish, Hungarian, Czech, Polish, Bosnian, and Estonian. It gained even more traction, after a right-wing American influencer online featured the claim on his show, mainly hosted on BitChute and Rumble. Clips of the show then circulated on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, with a Japanese translated version of the video garnering over 66,000 views.

Figure 3: Recurring COVID-19 misinformation spreader Alex Berenson shares a false claim that a Danish soccer player who suffered cardiac arrest had been vaccinated recently (left). A US-based mother’s wellness page shares a story about a Mexican woman who died shortly after receiving the vaccine with the caption, “She felt weak after the shot, passed out, and then died within 40 minutes of the shot, but her death isn't related to the shot. 😒” (center). A Spanish-language account shares criticisms from Michal Yeadon of vaccine passports, with the caption “The virus exists, but it is an excuse for total control of the population” (right, translated).

When content that spotlights potential harms related to vaccines or other more explicit anti-vaccine material gains traction internationally, it often involves a core group of US- and foreign-based influencers, including partisan media figures. Sometimes, these influencers or their followers immediately translate their content into English or other languages anticipating and engineering for international spread. And, as the Jacob Clynick case above illustrates, local anti-vaccine groups in varying countries can then take up the content, often framing it to fit the social and historical context of their community.

Global Circulation Prolongs the Longevity of Misinformation

Even though we can anticipate certain narratives and debunk them, the international spread of anti-vaccine content can help these claims persist in spite of these efforts. For instance, towards the end of May, an English-language user on Twitter falsely tweeted that “Airlines are meeting today to discuss the risks of carrying vaxed passengers due to the risk of clots and the liabilities involved. Oh the irony only the non vaxed can fly.” While the Associated Press debunked the claim and Twitter removed the original tweet, the claim had already circulated in a few low-quality news sites in Russian, German, and in Spanish. Then, in mid-June, a Chinese-language account tweeted a link to one of these stories, leading the claim to regain moderate traction in English on different social media sites. Other incidents that have resurfaced in English after circulating abroad include false claims that deaths in Israel skyrocketed from the Pfizer vaccine that have been fact-checked on numerous occasions and a recycled rumor that the Supreme Court had canceled vaccine mandates that resurfaced on Inspirer Radio, a Nigerian website, earlier this year.

Key Takeaways

The examples in this post illustrate how the international spread of misinformation contributes to the larger pervasiveness of anti-vaccine narratives and tropes. Local anti-vaccine groups and media outlets perpetuate narratives across borders. In particular, the collective experience around the COVID-19 pandemic makes local stories and pieces of misinformation salient to a global audience. This means that news of individual tragedy, which anti-vaccine influencers can strip of their context and use to undermine confidence in vaccines, can spread quickly across the globe. It also means that even after measures have been taken to deplatform or counter-message, particular misleading stories and false claims can resurface again after gaining traction abroad.